performance

curation

installation

printmaking

My aspiration is to bring about personal and collective healing, a more joyful society, and systems that empower us to care for each other and the earth. I thrive when I can apply a dynamic mix of skills and bring eight years' experience working with art and design studios, research institutes, international nonprofits and grassroots movements.

I combine different media and fields of study to explore questions or themes in open-ended ways. Often incorporating a participatory, performative, or curatorial element, projects act as containers for processes to unfold.

performance

curation

installation

printmaking

I intervene in culture to promote alternative ways of thinking and organizing. Inspired by strategic design, projects approach challenges with inquiry, analysis, and proposals for interconnected interventions.

strategy

visual

web

publication

I ask a lot of questions and make an active effort to learn about the ecologies I work within. More exploratory than systematic, my research practice usually stems from practical needs or personal interest.

design research

mapping

interviewing

I write fiction, nonfiction, and experimental combinations of the two. My writing practice enables me to share a perspective so others might experience it, resonate and respond.

articles

essays

stories

scripts

I organize workshops and participatory processes to achieve a collective goal or set of outcomes. Through my facilitation practice, I aim to help people connect and work together more effectively.

collaboration

organizing

workshops

These 9 themes offer insight into the central topics and intentions of my work.

For me, depth of learning comes not only through abstract sources of knowledge like books and media, but also participation in lively engagements like creative projects and working/volunteering/training in relevant contexts.

alter-economics

creative futuring

healing

material reuse

more-than-humans

re-enchantment

relationality

self-determination

urban systems

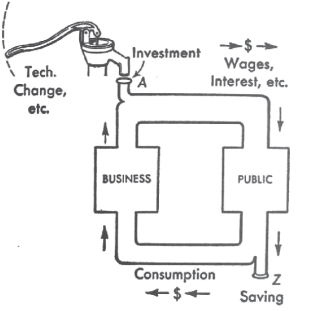

Alter-economics takes non-dominant or marginal perspectives on economics as its starting point. Financial markets are just one of many possible systems to meet needs and desires: alter-economies help us to exchange meaningfully with one another in ways that are different and often less visible than the money economy, but come with richer exchanges of value. Examples of alter-economies include the commons, mutual aid, gift economies, material reuse, trading systems, creative currencies, timebanks, and more. Many alter-economies operate relationally and are better suited to support sustainable collective organizing than the dominant extractive models of today. Decentering money positions us to diversify our systems, creating resilience in times of economic or environmental shock.

Kate Raworth, Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist. Random House: 2017.

Kakee Scott, “Performative Dynamics in Designerly Economics.” NERD – New Experimental Research in Design. Birkhäuser: 2022.

Creative futuring engages the radical imagination to envision and explore possible futures. It encompasses a wide range of creative takes on strategic foresight, and often employs artistic methods to make futures more tangible, emotive or engaging. Creative futuring can also be understood as sci-fi or speculative fiction placed in service to planning. Participatory futuring is a related term that emphasizes the participatory aspect of creative futuring, in which members of a community come together to collectively imagine, discuss, and strategize ways to achieve desired outcomes.

Rob Hopkins, From What Is to What If: Unleashing the Power of Imagination to Create the Future We Want. Chelsea Green Publishing: 2020.

Dark Matter Labs, “DM Note #8: On Art, Imagination Infrastructures, and Shared Memories of the Future.” Medium: 2022.

Healing involves tending to ruptures and restoring health and wellbeing, from the physical and mental to the emotional and spiritual. Healing is a continuous self-organizing process that can be helped along by conscious efforts of supportive presence, listening, and consistent experimentation within one’s window of tolerance. Examples of healing processes include the body’s natural inclination towards regeneration, the mind’s attempts to surface and process trauma, the heart’s yearning for authentic connection, and the spirit’s journey towards balance and wholeness.

Gabor Maté and Daniel Maté, The Myth of Normal: Trauma, Illness & Healing in a Toxic Culture. Ebury Publishing: 2022.

Connie Zweig and Jeremiah Abrams, Meeting the Shadow: The Hidden Power of the Dark Side of Human Nature. TarcherPerigee: 1991.

Richard C. Schwartz, No Bad Parts: Healing Trauma and Restoring Wholeness with the Internal Family Systems Model. Sounds True: 2021.

Material reuse involves recovering materials from existing products or structures and using them again in their original form for a new purpose (as opposed to recycling or discarding them). More than merely reducing waste or environmental impacts, reuse represents a different paradigm whereby the unique histories, properties and agencies of materials make them more valuable, not less. Reuse counters waste by extending material lifecycles and encouraging respectful relations with the material world.

Jane Bennet, Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Duke University Press, 2010.

More-than-humans are entities that exist beyond the realm of human beings, encompassing both living and non-living aspects. This includes animals, plants, fungi, soil, mountains and waterbodies, as well as spirits, deities, past/future generations, and even technologies like AI systems, digital infrastructures or prosthetic implants. Rather than consciousness or action, the term emphasizes the agency of the entity in our shared system: its ability to exert influence and affect outcomes, and our intimate entanglement with it. This perspective can help foster relationality because decentering human perspectives frees up greater consideration for the needs, values and contributions of all other entities. Being present with our more-than-human counterparts is a practice—one that ideally involves acts of care and integration of their wisdom into our own knowledge and systems.

Maria Puig de la Bellacasa, Matters of Care: Speculative Ethics in More Than Human Worlds. University of Minnesota Press: 2017.

Re-enchantment is the revival of a sense of wonder, meaning, and mystery in the world. It involves a shift away from the alienation produced by capitalist relations and scientific rationalism, towards a reconnection with nature, community, and cooperative forms of living and working. Where capitalist modes of production disenchanted the world by separating people from their communal ties, land, and traditional knowledge systems, re-enchantment calls for a revalorization of these suppressed knowledges, practices, and social bonds, alongside more holistic understandings of reality that foster reverence for nature and a sense of interconnectedness between humans and more-than-humans.

Silvia Federici, Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body and Primitive Accumulation. Autonomedia: 2004.

Morris Berman, The Reenchantment of the World. Cornell University Press: 2017.

John Welwood (Editor), Ordinary Magic: Everyday Life as Spiritual Path. Shambhala Publications: 1992.

Relationality refers to connectedness: a worldview in which nothing exists in isolation, because existence happens through relationships. This philosophy implies an ethics of tending to the people, places, and relational ties in our lives through deliberate acts of presence, empathy and care. While relationality is an Indigenous term, similar principles can be found throughout diverse traditions ranging from science to spirituality. Connectedness is the underlying logic of complex systems theory, which teaches relationality via systems thinking. In Buddhism, relationality flows through concepts like pratītyasamutpāda (“dependent co-arising”) and anattā (“non-self”). Being socialized into settler philosophies and systems, my understanding of relationality was shaped primarily by Indigenous scholarship. This knowledge is transmitted orally and through embodied cultural practices, so my understanding is incomplete, but I have found great wisdom and inspiration in Indigenous teachings like the Okanagan’s four capacities of self, which cultivate relational cultures, belief systems and organizing principles.

Arturo Escobar, Designs for the Pluriverse: Radical Interdependence, Autonomy, and the Making of Worlds. Duke University Press: 2018.

Jeanette Armstrong, “Sharing One Skin: The Okanagan Community.” The Case Against the Global Economy, Sierra Club Books: 1996.

Self-determination is the capacity to make choices and govern one’s own life free from oppressive systems or authoritarian control. It emphasizes freedom of choice, responsibility for decisions that affect one’s existence, and accountability to those whose lives are entangled with our own. On an individual level, self-determination is the ability to live in a way that honours personal values, relational ties, dreams and desires, and pursue work that gives a sense of autonomy and purpose. On a collective level, it is the right for members of a community or nation to decide their own culture, policies, and governance without violent or coercive interference from non-members. Self-determination is an important concept in law, as well as decolonization, the process by which colonized societies gain sovereignty and establish self-governance.

Marylène Gagné and Edward L. Deci, “Self-determination theory and work motivation” (2005). Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26, 331–362.

Urban systems are the interconnected networks of pathways and protocols that make cities navigable. These practices, services and infrastructures enable us to live well together in a place, sharing resources efficiently and helping each other thrive. Yet many of the systems that define our shared existence are extractive and exclusionary, driven by private interests that favor profit over collective wellbeing. For example, under the system of “real estate” that governs our social, legal, and fiscal relationships to land, the right to profit off privatized land takes precedence over the basic human need for shelter. There can be no ecological transition without first recognizing the perverse incentives built into existing systems and exploring how we might organize otherwise.

David Madden and Peter Marcuse, In Defense of Housing: The Politics of Crisis. Verso Books: 2017.

If you have an idea for how we could work together or if you just want to connect, I’d love to hear from you.

I’m especially interested in exploring collabs with...

Email me: maddy.capozzi[at]hotmail[dot]com